APPELLATIONS AND CLASSIFICATION IN SAINT-ÉMILION

Facts are facts but any otherwise unattributed opinions, express or implied, on this page are those of the Chancellor in the North in his personal, not official, capacity and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of any other person or body connected with the Jurisdiction . . .

Appellations d'Origine Controlées — now Appellations d'Origine Protegées

The Jurisdiction of Saint-Émilion is unusual in that, since 1984, it has had two Appellations d'Origine Controlées (AoC) each covering exactly the whole of the geographic area of the Jurisdiction: Appellation d'Origine Controlée Saint-Émilion and Appellation d'Origine Controlée Saint-Émilion Grand Cru.

Strictly speaking, from 1st August 2009, as a result of pan-European changes of wine laws, these have become Appellation d'Origine Protegée Saint-Émilion and Appellation d'Origine Protegée Saint-Émilion Grand Cru, Appellation d'Origine Protegée usually being shortened to AoP in the same way as the old AoC. It is however correct to say that the old terms are still in use not only in France but more generally. The AoC or AoP Saint-Emilion Grand Cru is also unusual in that the Appellation is not given to the terroir or the estate where grapes are grown but is decided each year. Subject to minimum density of vines, maximum permitted yields and minimum alcohol levels, any wine made from the approved varietals (merlot, cabernet franc sometimes still called bouchet locally, cabernet sauvignon, malbec known here as Pressac, petit verdot and carmenère) grown in the Jurisdiction is entitled to the Appellation d'Origine Controlée or Protegée Saint-Émilion. For many years, subject to the relevant minimum density of vines, maximum permitted yields and minimum alcohol levels, a grower who made the wine in the Jurisdiction and thought it sufficiently good, could submit it to a tasting in the year after it was made for a certificate that it had the capacity to age. If that was granted, the wine had again to be submitted for further tasting in the following year to see if it had the capacity to age well and, if approved, that wine of that vintage was allowed to bear the higher Appellation of Grand Cru, subject to an obligation for it to be bottled at the Château.

Amongst all the AoCs/AoPs in France, only that of Saint-Émilion Grand Cru required such dual tasting. The rules had been more relaxed in recent years but tasting has been re-introduced so that this unique requirement once again plays its part in making the Jurisdiction stand out in its concern for quality.

The result of this system is that there is no fixed list of Grand Crus Châteaux – anyone thinking of buying needs only consult the bottle, not a book, to see which Appellation the wine enjoys and will then have the comfort of knowing that its quality is specific to that vintage.

It is, however, also well worth bearing in mind that some wine which would qualify as Grand Cru is not submitted for that Appellation because the grower does not wish to sell his wine as such. There is a number of examples of growers making two wines but not wishing both to be in the same category where they would compete against each other.

There are also occasions when a grower of a classified growth may decide that he will not sell his wine as such in that year (avoiding it being judged as the classified wine at reclassification). If he makes that decision the wine is sold as Saint-Émilion not as Saint-Émilion Grand Cru. It is still likely to be very good and offer even better value than other wines of the same technical description.

Similarly there are wines grown in, but made outside, the Jurisdiction, or not bottled at the château, which do not qualify to be submitted for the Grand Cru Appellation but which are in every other way of similar quality to those which do qualify. Again these are often exceptionally good value for money for the consumer.

Premier Grand Cru Classé and Grand Cru Classé

Saint-Émilion had no part in the 1855 Left Bank classification and had no classification system of its own until 1955.

Unhandicapped by an old system, it was able to create a modern one. Within the higher Appellation of Saint-Émilion Grand Cru, there are two levels of classified growth - Premier Grand Cru Classé (itself sub-divided into "A" and "B") and Grand Cru Classé.

The classification takes place anew about every ten years, both for those already classified and those wishing to be so, so that there is a complete review. It has not been true , as some critics thought would be the case, that the numbers of classified growths would increase with each review. Indeed rather the reverse has happened, especially in the case of the Grands Crus Classés. In 1955 there were 12 Premiers Grands Crus Classés and 63 Grands Crus Classés. Whilst 1969 saw a further 9 Grands Crus Classés added bringing the total to 72, the 1986 review gave only 11 Premiers Grands Crus Classés and 63 Grands Crus Classés. Ten years later, in 1996, there were 2 new classifications as Premiers Grands Crus Classés, giving a total of 13, but only 55 Grands Crus Classés emerged from the review. The proposed 2006 classification, surrounded by controversy and eventually judicially overturned, would have seen a further decline in the latter's numbers to 46, when Ch. Pavie-Macquin and Ch. Troplong Mondot each became Premier Grand Crus Classé

The 2012 Classification increased the number of Premiers Grands Crus Classés to 18 and of Grands Crus Classés to 64;

The 2012 list had 18 Premier Grand Cru Classés, with four at ‘A’ status, and 64 Grand Cru Classés.

The 2022 Classification has left us with 14 Premier Grand Cru Classés, with two at Premier Grand Cru Classé A status, and 71 Grand Cru Classés.

In 2022 the announcement had been preceded by surprise rather than in itself occasioning it. In the previous year Châteaux Cheval Blanc, Ausone, La Gaffeliere and Angélus had all withdrawn. The first two were unhappy about the account taken of marketing and wine tourism infrastructure in the process introduced in 2012, believing that terroir and wine quality were very much undervalued by the process.

La Gaffeliere withdrew when questioned at short notice about the quality of its terroir, pointing out that no such question had been raised in 2012 under the same rules or in any previous classification. It also asserted that the rankings given to its wines by the Commission's tasters “contradicted all the ratings of the world's greatest wine professionals”.

Angelus withdrew in January 2022 saying that it had come to believe that the classification system had become “a vehicle for antagonism and instability.”

These withdrawals have taken place despite a change in the rules which gave 50% of the marks to the results of a blind tasting by an independent panel. That was up from 30% for PGCCs in 2012, although, of course, any candidate for PGCC would also have had to get through the GCC tasting where 50% of the marks were allocated to tasting.

What many perceived to be injustices from both 2006 and 2012 have been remedied in that Ch. Figeac has now become PGGC “A”, after long being denied that rank on “the sole ground” that it was not selling at the same price as Cheval Blanc and Ausone; a ground which many felt those less loyal to Saint-Emilion that the Manoncourt family might well have challenged as anti-competitive, as well as inherently illogical.

Château Canon, now benefitting from the enormous work done by John Kolasa when he was in charge, was not promoted as many had expected, nor was Château Troplong Mondot.

It is among the ranks of the Grand Cru Classes that there has been most change, with the promotion of Clos Dubreuil, Château Tour Saint Christophe, Château Lassegue, Château Tour Baladoz, Château Rol Valentin, Château Mangot, Château Le Croizille, Château La Confession, Château Boutisse, Château Croix de Labrie, Clos Saint-Julien (showing being small does not matter), Clos Badon-Thunevin, Château Montlisse, Château Badette and Château Montlabert. What many perceived to be a gross injustice in 2012, the demotion of Château Corbin Michotte, has been reversed and it is back as a Grand Cru Classé. It had always been a very long standing Grand Cru Classé but failed to keep its official place as such, although it had come second, judged by its peers, only months before in the official Coupe des Grands Crus Classés, (incidentally beating Ch. Canon la Gaffelière which was of such quality as to be promoted to Premier Grand Cru Classé in that revision.)

A list of the classified wines follows, alphabetically, with an asterisk marking the additions or restoration to any particular class compared with the 2012 list:

Premiers Grands Crus Classés

A: Ch. Figeac*, Ch. Pavie;

B: Ch. Beauséjour (Duffau Lagarrosse), Ch. Beau-Séjour-Bécot, Ch. Belair-Monange (formerly Ch. Belair and now including the former Ch. Magdelaine ), Ch. Canon (now including the former Ch. Matras), Ch. Canon la Gaffelière, Clos Fourtet, Ch. Larcis Ducasse, La Mondotte, Ch. Pavie-Macquin, Ch. Troplong-Mondot, Ch. Trottevieille (now including the former Ch. Bergat), Ch. Valandraud.

Grands Crus Classés:

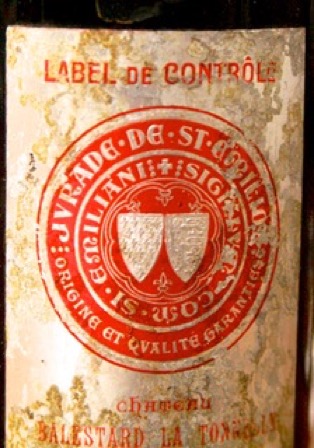

Ch. Badette*, Clos Badon Thunevin*, Ch. Balestard la Tonnelle, Ch. Barde-Haut, Ch. Bellefont-Belcier, Ch. Bellevue, Ch. Berliquet, Ch. Boutisse*, Ch. Cadet Bon, Ch. Cap de Mourlin, Ch. le Chatelet, Ch. Chauvin, Ch. Clos de Sarpe, Ch. Corbin, Ch. Corbin Michotte*, Ch. Cote de Baleau, Ch. la Confession*, Ch. la Commanderie, Ch. La Couspaude, Ch. Croix de Labrie*, Ch. Dassault, Ch. Destieux, Ch. La Dominique, Ch. le Croizille*, Ch. Faugeres, Ch. de Ferrand, Ch. Fleur-Cardinale, Ch. La Fleur Morange, Ch. Fombrauge, Ch. Fonplégade, Ch. Fonroque, Ch. Franc Mayne, Ch. Grand Corbin (which now takes in the former Ch. Haut Corbin), Ch. Grand Corbin Despagne, Ch. Grand Mayne, Ch. Guadet (formerly called Ch. Guadet Saint-Julien), Ch. Haut Sarpe, Clos des Jacobins, Couvent des Jacobins, Ch. Jean Faure, Ch. Laniote, Ch. Larmande, Ch. Laroque, Ch. Laroze, Clos la Madeleine, Ch. La Marzelle, Ch. Mangot*, Ch. Monbousquet, Ch. Montlabert*, Ch. Montlisse*, Ch. La Serre, Ch. Lassegue*, Ch. Moulin du Cadet, Clos de l'Oratoire, Clos Dubreuil*. Ch. Peby Faugeres, Ch. Petit Faurie de Soutard, Ch. de Pressac, Ch. Le Prieuré, Ch. Ripeau, Ch. Rochebelle, Ch. Rol Valentin*, Ch. Saint-Georges-Côte-Pavie, Clos Saint-Julien*, Clos Saint-Martin, Ch. Sansonnet, Ch. Soutard, Ch. La Tour Figeac, Ch. Tour Baladoz*, Ch. Tour St. Christophe*, Ch. Villemaurine, and Ch. Yon Figeac.

Keen observers will note, in some cases with very great sadness, that a number of names no longer appear:

Château Pavie-Decesse is merged with the contiguous Château Pavie;

Château les Grandes Murailles with contiguous Clos Fourtet;

Châteaux L’Arrosée and Grand Pontet have been swallowed by the Quintus empire;

Château la Clotte and Quinault L’Enclos have each withdrawn with their respective sister estates Châteaux Ausone and Cheval Blanc.

Clos la Madeleine in the same ownership as Belair-Monange, is not in the list and nor is Faurie de Souchard, owned by Château Dassault: it seems likely that their vines will be included in their owners' other wine.

Château Croque Michotte (demoted in 2006 and 2012, and the unwilling benefactor of many lawyers since then,) withdrew when it became clear that they were not likely to be re-promoted with its owner Pierre Carle saying, ‘I will not go to the commission to dispute with people who don’t know what they are talking about. Either we are classified, or it’s war’.

Classification, criteria - and controversy

Any classification system is human and is bound to be subject to controversy and criticism and this has certainly been true of Saint-Émilion's as well. Inevitably decisions have a subjective element and in a wine world of partisan championship of different styles, arguments will arise. More importantly, wine invites love - and wine lovers who feel a particular beloved has been slighted or overlooked will inevitably be furious on its behalf. Litigation can follow the announcement of the Classification Committee's decisions and four Châteaux challenged the 2006 classification.

The same was true of the 2012 classification in respect of which three Châteaux made a legal challenge. The principle of classification itself was not challenged, the issue was the judgement of the Commission in individual cases.

The 2006 challenge led to the suspension by a first instance Court, upheld on appeal in March 2009, of the whole classification. The suspension left a vacuum, pending the next reclassification procedure, with no grower lawfully being able to rely on the previous classification as currently valid. In order to alleviate that problem for most, pending a new and valid classification, a Ministerial decree initially revived the 1996 classification for 2006 to 2009 which, of course, left everybody with the status they then had. Whilst that relieved the difficulty for most Châteaux, it was, on any view, very hard on those who had been found to merit promotion. In May 2009 the Government effectively added those Chateaux which had been designated to be promoted in the 2006 classification to the 1996 one, finally removing that problem. Government intervention therefore approved promotions proposed by the 2006 classification but left overturned its proposed demotions.

The 2006 classification gave rise to further controversy, although it did not lead to legal action on this ground, because the Committee’s interpretation of the requirement in the rules that it should take into account price, led to several Châteaux being denied a higher classification on the sole ground (le seul motif) that they sell at too low a price - it is well known that Ch. Figeac, a Premier Grand Classé B, was refused promotion to join Ausone & Cheval Blanc as Premier Grand Classé A for this reason alone, a decision widely criticised in the English speaking world.

Moreover, some Châteaux had been in the process of improving markedly under new ownership or direction but were still demoted, presumably because they were thought to have been less good during the early part of the relevant period - Château Bellevue, for example, was widely thought to be in this category as were some of those who, unlike that Château, took legal action.

Those facts simply underline what anyone concerned with a classification system recognises, that elements of subjectivity and personal judgement, perhaps unwittingly influenced by style preferences, can play a part and those looking for wine would, as always, be well advised to be more influenced by the contents of a bottle than by its label. Nonetheless, whilst there will always be room for discussion and debate, the system provides some assistance for customers new to, or not very familiar with, the Jurisdiction's wines as well as wider public recognition of the especial excellence of those classified, even when there are strong arguments for saying that there are others of equal quality whose merits have not been officially recognised or as fully recognised as they deserved. It is also worth bearing in mind that the system of scoring, outlined below, takes into account matters other than the quality of the wine so that what many regard as very good wine may not qualify because other criteria than quality are judged not to be met.

Decanter’s article on the 2012 results provides one interesting independent Anglo-Saxon viewpoint: here

The new Criteria

Following the problems with the 2006 classification, a review of the rules for classification took place, not by the Saint-Emilionais themselves but INAO, the central French wine authority. The new rules were promulgated on 6th June 2011 by ministerial order and the 2012 classification process took place under them. They were amended slightly for 2022 as noted above in relation to the PGCC tasting marks.

The rules can be found in French here

They governed the 2012 classification and there was an independent Classification Commission composed of members of the INAO National Committee or those chosen for their special competence. There was thus much less local involvement under these rules than before and anybody with a direct interest in the classification was barred, thus preventing negociants being directly part of the process. Whilst that provides independence it may also be said to deprive the system of some very well attuned Bordelais palates familiar with the wines of the Jurisdiction. Some have suggested that the whole process would acquire greater international authority if named and renowned palates took part in the blind tasting, perhaps as part of an appeal process.

Up to fifteen years’ vintages may be taken into account for Premiers Grands Crus Classés and ten for Grands Crus Classés.

An application has to be made by the grower supported by a dossier covering the activities of the relevant ten or fifteen year period.

Applicants' wines are marked out of 20 with a requirement to obtain 14/20 for classification as Grand Cru Classé and 16/20 for Premier Grand Cru Classé. The marks awarded are not made public, so there can be no classification within a classification.

Mark allocation for Grand Cru Classé:

50% of score for tasting.

20% for national and international reputation, their own promotional activities, wine tourism activities, accessibility for the public, and distribution methods.

20% for terroir.

10% for winemaking and viticultural techniques, traceability and ageing capacity.

Mark allocation for Premier Grand Cru Classé:

(All must first be adjudged to be worthy of Grand Cru Classé – although they do not have to have been so classified in the past)

50% of score for tasting

35% for national and international reputation, their promotional and wine tourism activities, accessibility for the public, and distribution methods

10% for terroir

5% for winemaking and viticultural techniques, traceability and ageing capacity.

The decision as to whether a Premier Grand Classé should be A or B depends, according to the rules, only on its reputation or fame and whether it has exceptional capacity to age. There is no requirement for a particular higher mark out of 20 for this distinction, whether specifically on tasting or overall, as there is for other gradations in the classification nor, despite the requirement for capacity to age, is any longer period than 15 years taken into account or older wines tasted. It is noticeable that Ch. Figeac, the capacity of which to age for periods far in excess of 15 years can hardly be in doubt, was not promoted to A in 2012. Equally the author of this note has been privileged to drink then 70 year old Ch. Ausone 1949 as well as both 1947 and 1949 of what was Beau-Séjour-Dr-Fagouet until bought by Michel Becot in 1969, as well as 1947 La Carte (famously incorporated by him into Beau-Séjour Becot). Al the wines had aged wonderfully with none showing at that stage of their life any greater ability to have done so than the other, suggesting that if long life is a criterion there may be many other Chateaux being overlooked!

There is provision for a re-examination of individual cases with a grower having a right to be heard.

The requirement that an applicant's wine should have been Grand Cru for seven out of the ten relevant years has gone in the new rules but the candidate vineyard must over the relevant period have produced an average of at least 50% of the wine under the same name as that which is the subject of the application. In order to qualify for consideration the estate also has to be a sufficiently large economic and viticultural unit and have cellars used exclusively for the candidate wine.

On pain of being declassified, candidates have to undertake that, for the following ten years, they will not, without proper authority, modify in any way the property on which the classified wine was made, and must also undertake to bottle it at the Château.

Please contact us if we can help or if you would like to know more about the British Association either by clicking on the links on the right of each page

or by e-mailing York@Jurade.org.uk or London@Jurade.org.uk